Rise Of Prussia Political Cartoon

Populism Political Cartoons. Populists' major complaint was that politicians and Wall Street held the 'people' down by manipulating the political system. This problem could be solved by a 'rising of the people' that would restore popular control of government. 1848; the future of the political cartoon lay not in independence, but in ab- sorption. Of phenomenal growth in Germany and from virtually nothing had emerged.

Get exclusive access to content from our 1768 First Edition with your subscription.The union of Ducal Prussia with Brandenburg was fundamental to the rise of the Hohenzollern monarchy to the rank of a great power in Europe. John Sigismund’s grandson of Brandenburg, the Great Elector (reigned 1640–88), obtained by military intervention in the of 1655–60 and by diplomacy at the (1660) the ending of Poland’s suzerainty over Ducal Prussia.

This made the Hohenzollerns over Ducal Prussia, whereas Brandenburg and their other German territories were still nominally parts of the Reich under the theoretical suzerainty of the Holy Roman emperor. Frederick William was also able to set up a centralized administration in Prussia and to wrest control of the duchy’s financial resources from the nobility.

Frederick William I, detail from a portrait by Antoine Pesne, c. 1733; in Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam, Germany. Foto Marburg/Art Resource, New YorkFrederick William I endowed the Prussian state with its military and character. He raised the army to 80,000 men (equivalent to 4 percent of the population) and geared the whole organization of the state to the military machine. One half of his army consisted of hired foreigners. The other half was recruited from the king’s own subjects on the basis of the “canton system,” which made all young men of the lower classes—mostly peasants—liable for military service. While the upper was exempted from military service, the nobles were under a obligation, which the king repeatedly emphasized, to serve in the officers’ corps.The close coordination of military, financial, and economic affairs was complemented by Frederick William I’s reorganization of the administrative system, and he came to control the whole life of the state.

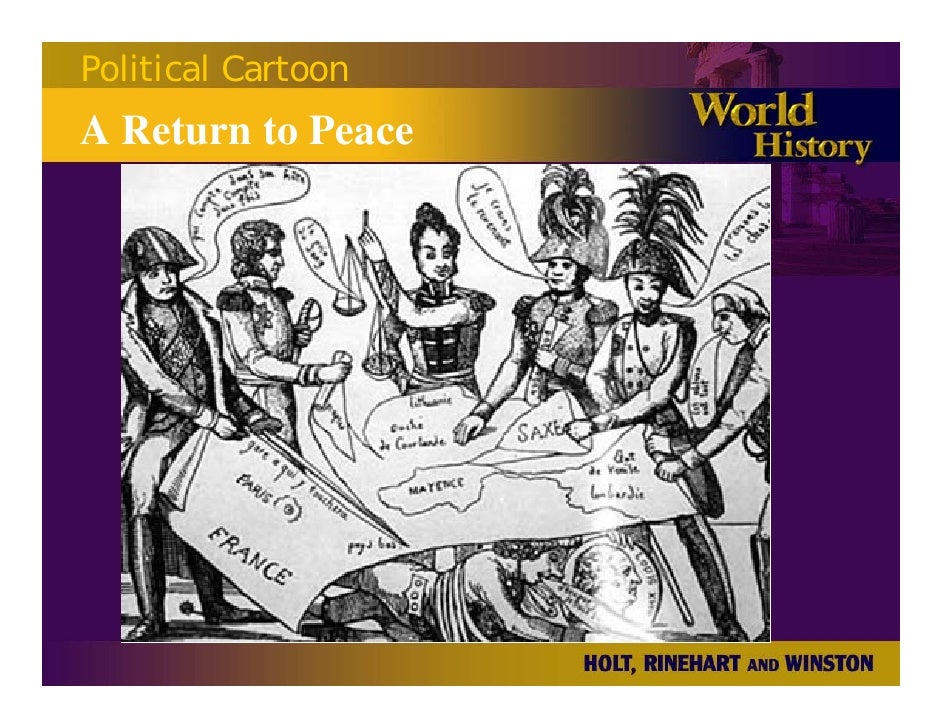

His autocratic temperament and his fanatical addiction to work found expression in complete. To his son and successor, he left the best-trained army in Europe, a financial reserve of 8,000,000 thalers, productive domains, provinces developed through large-scale colonization (particularly East Prussia), and a hardworking, thrifty,.Frederick II (reigned 1740–86) put the newly realized strength of the Prussian state at the service of an ambitious but risky. Hailed by as “the philosopher king” personifying the and its ideal of peace, Frederick astonished Europe within seven months of his accession to the throne by invading in December 1740. This bold stroke precipitated the, and the continued, with uneasy intermissions, until the end of the in 1763. Silesia, a rich province with many flourishing towns and an advanced economy, was an important acquisition for Prussia. Frederick’s wars not only established his personal reputation as a military genius but also won recognition for Prussia as one of the Great Powers. Poland, First Partition of A cartoon depicting the monarchs of Europe—notably Catherine II of Russia, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, and Prussian King Frederick William II—at the First Partition of Poland.

Clicker war. British Cartoon Prints Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Art of conquest races. (digital file no. 3g06750)Frederick made no substantial changes in the administrative system as organized by his father, but he did effect improvements in the judicial and educational systems and in the promotion of the arts and sciences. The freedom of that Frederick instituted was the product not merely of his own skeptical indifference to religious questions but also of a deliberate intention to bring the various churches together for the benefit of the state and to allow more scope to the large Roman Catholic minority of his subjects in relation both to the Protestant majority and to the Evangelical establishment.